I have been building my U.S. Part 135-involved accident database for a few months and it’s time to talk about what’s missing in too many accident investigations.

Ameriflight Beech 99 in Lansing, MI August 2023; 1 minor injury.

Right now, for the five year period between January 1, 2019 and December 31, 2023, I have found 280 accidents involving Part 135 operators. These crashes resulted in 151 deaths and 80 serious injuries. The database is not yet complete however, as I am still checking through accidents classified as Part 133 (Helicopter Exterior Load) or Part 91 (General Aviation such as Positioning, Instruction, etc.) which involved Part 135s.1

As you can imagine, this research is quite tedious as and requires at least glancing at every single possible Part 135-involved accident over a five year period. (That means thousands of accidents.) But if I want the database to be complete, it’s necessary. In my opinion, it is crucial to review all accidents a Part 135 commercial operation is involved in to fully understand the company. As an example, consider that Guardian Flight, an air ambulance that operates all over the country, was involved in four accidents between 2019 and 2023. Two of them were under Part 135 but the others, one near Kake, Alaska and one in Kaupo, Hawaii, were classified as Part 91: Positioning because the patient had not yet been picked up. (For Guardian, that made them nonrevenue flights.) Along with a 2023 accident in Nevada, the Alaska and Hawaii accidents resulted in eleven fatalities. If you only checked the Part 135 listings in the NTSB database, you would miss the Alaska and Hawaii crashes and a key part of what was going on with the company2.

What I’m looking for, what anyone reviewing accident reports is likely looking for, is patterns. It might be patterns with aircraft type or pilot flight time; it could be cause of accident or location. For Guardian Flight, it is both the type of operation (medevac) and the company which jump out at me. (As I go through the accidents I am entering those that apply into a separate medevac database as well. I have a lot of questions about medevac ops.) When I wrote about cargo carrier accidents last year for AIN it was because I was seeing something in the NTSB database in that segment of the industry and wanted to know more. I started pulling data for crashes involving cargo carriers and found a story. But even then, I didn’t find everything I was looking for.

What investigators are not asking

The photo at the top of this newsletter is for Ameriflight #1304, a 2023 cargo flight scheduled from Lansing, Michigan to Sault Ste Marie. The pilot was on reserve from 6:15AM; at 6AM he was informed another pilot was ill and thus he would be flying #1304 and also adding a first stop, to Pellston. According to his statement he had never been to either airport; he flew along on a familiarization flight around Lansing only the previous weekend.

The accident report is very short - he was cleared for takeoff, weather not an issue, the aircraft started “drifting” on the runway as he added power; at 30ft in the air it started rolling to the right, he added left rudder, could not compensate and crashed while attempting to land on the taxiway. This statement from the report explains what went wrong: “Prior to exiting the airplane, the pilot noted that the rudder trim was set to the full nose-right position.” The Probable Cause was “..failure to properly set the rudder trim position which resulted in a loss of directional control during takeoff. Contributing was the pilot’s inadequate checklist procedures prior to takeoff.”

This occurred before the flight which explains things a little bit:

The pilot provided a two-page statement which is the only insight into company operations and it had a couple of things that stood out. First, was the fact that he had never flown out of Lansing or into the other two destinations. This passage, which refers to Pellston and Sault Ste. Marie, is worth reading:

These are both unfamiliar airports to me, so I tried to look up their information in the Airport Briefing Guide so as to know what to do upon arrival at each place, and look for any procedures specific to these airports. Shortly after arrival to the plane I looked over the maintenance logbook for the aircraft. Everything seemed good, and the next maintenance item would not be due for multiple days. I then finished the Originating Checklist and while I was finishing UPS arrived and started to load my aircraft while I was trying to complete my walkaround.

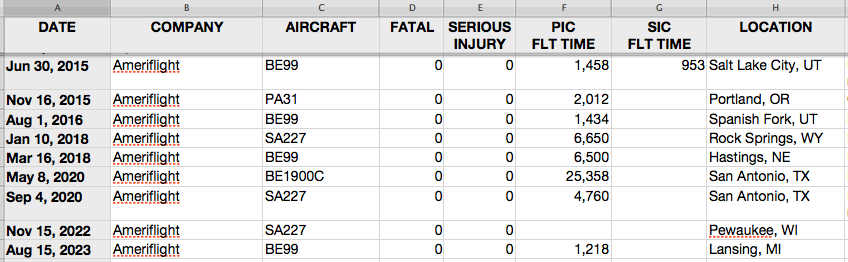

And then there is this: he had 1,218 hours of total time but only 26 in the Beech 200. He also had less than 400 hours of total PIC time. Combined with unfamiliarity with Lansing operations and his destinations, UPS loading while he was still getting ready, and coming in from reserve which meant he didn’t have hours of prep time, the failure to check the rudder trim becomes understandable. (I’m not excusing, I’m understanding.) (This is all called “task overload” if you are wondering.) But then I take a step back and look for larger patterns, and is where I find this in my cargo operator database (which goes back to 2015):

There were also three more accidents from Ameriflight’s sister company (same ownership, still Part 135), Wiggins Airways, in March 2016 (turbulence encounter, no injury), August 2023 (flight training, two fatalities) and January 2024 (a crash soon after takeoff with one serious injury).

I see a pattern here and I would expect that the NTSB does as well. That is why I would also expect that when the Beech 99 crashed in Lansing, investigators would have interviewed company management to see if there was some company-wide issue with training or operational control going on. That did not happen. I would also have expected interviews with the company’s FAA inspectors, especially the Principal Operations Inspector (POI). That didn’t happen either.

While the two recent Wiggins accident investigations are still open, and thus any possible interviews have not been released, there is no record of any interviews with company or FAA personnel in any of the Ameriflight accidents.

Which brings me to this:

On October 7 an Ameriflight Beech 99 crashed shortly after departing Norfolk, NE enroute to Omaha with a load of cargo. The pilot was killed. From the preliminary report we know: “Airport surveillance video captured the airplane as it departed the airport. The airplane departed from runway 20 and climbed away from the ground. The airplane then entered a left bank turn, descended, and impacted terrain.”

There was a post impact fire.

We will have to wait at least a year for this final report where, hopefully, the NTSB will have some interviews with the Ameriflight Chief Pilot and Director of Operations, and FAA officials. If there is anything to be gleaned about the company’s operational oversight and safety culture, it would be discussed then. (If I was researching Ameriflight for an article, in light of this accident, there are some specific FOIAs I would be requesting right now.)

What else am I looking for?

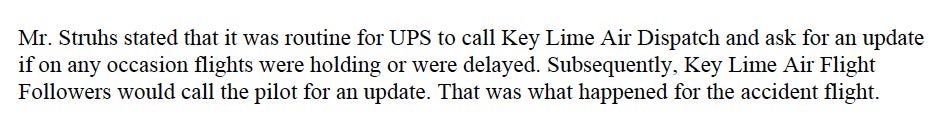

Remember the newsletter I released in April on Key Lime Air Flight 308? That accident also involved a cargo Part 135 flight, this time from Panama City, FL to Albany, GA in December 2016. The pilot, who was the sole employee based in Panama City, was on a self-imposed weather hold due to thunder storms in the area. He spoke with a company dispatcher based in Colorado at about 8:30PM, an hour prior to departure, notifying him of the situation, which included the threat of tornados in the area. After a phone call with a different company dispatcher at 9:42PM, (the two dispatchers fielded multiple round of calls from UPS in this period), the pilot informed him that he could depart. Flight #308 took off at 9:54, quickly ended up having to divert, and crashed less than a half hour later. The pilot did not survive.

This investigation included several interviews with company personnel including the two dispatchers. According to the first, who spoke with the pilot at 8:30PM, he received three phones calls from the same UPS employee after flight #308 was put on hold. He did not remember that person’s name, however. In the first call, he said, the UPS rep wanted to know if the pilot “was going to be able to make it to Albany.” In the second call he was asked again if the pilot was going to make it as “UPS employees in Albany had not seen the aircraft yet.” When the third call arrived he informed UPS that he was not sure what was happening as Key Lime’s flight tracker was showing the aircraft diverted to Tallahassee. (This was the pilot’s attempt to avoid what had become a wall of thunderstorms.) By then, the plane was down.

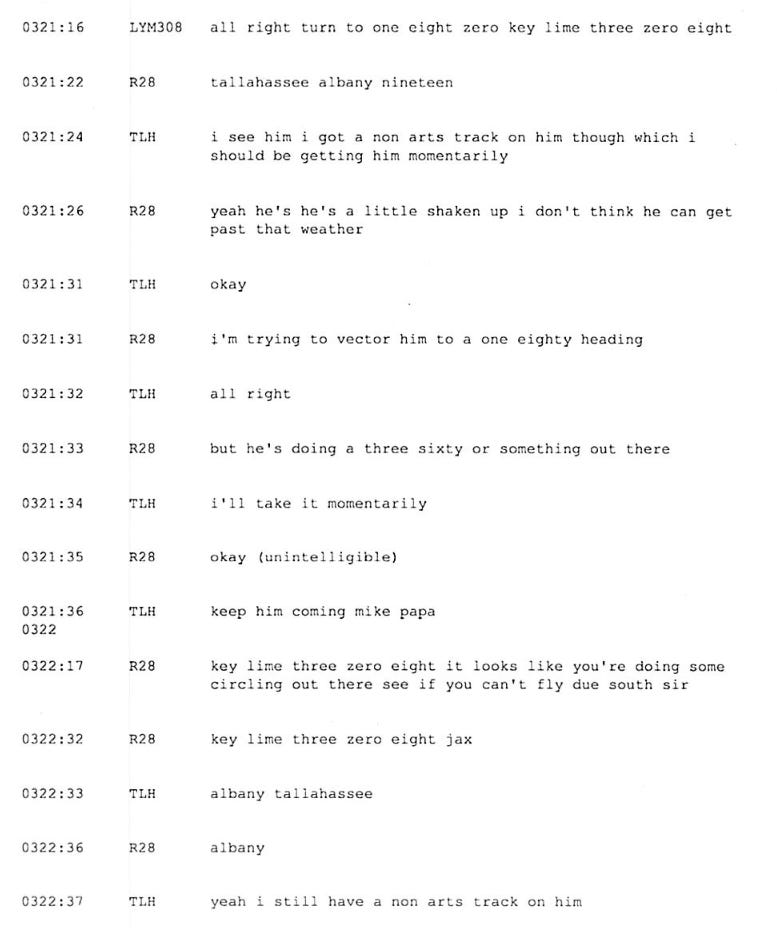

The second dispatcher was not assigned to flight #308 but he also interacted with UPS about the flight. He answered a call around 9:30PM where a UPS rep noted it was “a while after when he [the Albany flight] was supposed to depart” and asked whether or not flight 308 was going to takeoff. He told the rep (whom he did not identify by name), that the flight was on weather hold. He then phoned the pilot at 9:42PM who, he said, told him he found a clear line and was planning to depart in a few minutes. That was last communication between the company and the pilot. He died, according to the ATC transcript, while he was trying to evade a line of extreme precipitation and land in Tallahassee. Here’s a bit from the end of the transcript:

The communication at the top of the page, acknowledging an assignment to 180 heading, is the last thing from flight #308. As for the Key Lime Air dispatch procedure, there is also this:

The NTSB does not have interview transcripts in the docket for this accident. There are summaries for some interviews and conversation records with other company personnel and management. The only communication record with Key Lime Air’s POI is two lines long and notes simply that it was the only company for which he had oversight responsibility. There is no record of any contact with UPS or even any attempt to find the employee who phoned Key Lime’s dispatchers four times in less than an hour asking again and again why flight 308 was running late. UPS, for all intents and purposes, was no part of this investigation. And, of course, the only assurance that the pilot was not pressured in any way by the company dispatchers is via the statements from the dispatchers themselves.

The Probable Cause for the crash of flight 308 was laid entirely at the feet of the pilot: “The pilot's decision to initiate and continue the flight into known adverse weather conditions, which resulted spatial disorientation, a loss of airplane control, and a subsequent in-flight breakup.”

It is not only what an investigation determines, but what it fails to consider

Obviously, not all accidents require in depth investigations with multiple interviews. For example, I don’t think investigators needed to talk to many folks after this Metroliner taxied out of the hangar in Smyrna, Tennessee, only to have a water main bust under the ramp causing a sinkhole to suddenly appear under its left gear. (This picture never gets old for me.)

But the many serious, even fatal accidents like Key Lime Air flight #308, where there is a lack of interviews or incomplete interviews, is really quite startling. Hands down, this has been the biggest shocker for me in working on my databases.

The more time I spend going deep on Part 135-involved accidents, the more I discover that there are not just patterns in what the data contains, but also in what it lacks. In cargo accidents I rarely find mention of the customer. Often, it is only through news reports that I’ve learned that a flight was carrying UPS or FedEx packages or served as a contracted feeder flight. In most cases however, the customer is a mystery. Investigators are thus missing the opportunity to discover if pressure from outside the Part 135 operator is an issue. The fact that no one at UPS was interviewed in the Key Lime Air case was especially mystifying. And as someone who can recall being phoned repeatedly by a customer demanding to know where an incoming flight is, well, the pressure can be very real. (Where I worked, we did not burden the pilots with knowledge of such communications.) (This meant I got yelled at over the phone a lot.) (There are stories I could tell you about the USPS in rural Alaska that you would not believe.)

The biggest thing I have found though is how infrequently the FAA is questioned in an accident investigation. Of the 280 crashes I presently have in my database, less than a dozen involve interviews with FAA inspectors and/or Flight Standards District Officers managers. If these individuals are overburdened, overwhelmed, complacent, ignorant, or exceptionally good or bad at their jobs, it is impossible to know. And the thing is, this is information we need to know and I am determined to find out. This is the biggest part of my research right now and something you will be reading more about this year and into the next.

I am quite certain that if more interviews were conducted over accidents that involved loss of control or poor decision-making where the pilots lived, more serious or fatality crashes would be prevented. There are a lot of dead pilots in my databases, but Part 135 operators continue to crash. At some point, you have to look in places other than the cockpit for answers. I’m finding mine in the creating spreadsheets that look for a lot of information. And even when I have to accept that questions were not asked, I’m still gaining answers one entry at a time.

Back for more on many things after the election. GO VOTE!!!!

If you’re wondering how I’m doing after winning the court case, I’m still having trouble with what that thing did to me. I’m writing but not nearly enough. I’m trying to figure out what future in journalism can even exist for me. I’m…unsettled. It’s going to take awhile to move on. Also, we are only in the earliest stages of getting any fees back and the cost has been so high. (And yes, an appeal from the Plaintiff is still possible.)

I include Part 133 and Part 91 flights that involved Part 135 operators because they contribute to the overall flight safety picture of a company. Also, a lot of folks don’t realize that a Part 135 flight can have legs that are Part 91 - for example the multiple fatality Guardian Flight crash near Kake, Alaska, in 2019 was classified Part 91 just because the company had not picked up its revenue patient yet. As for Part 133, it’s not uncommon for Part 135 helicopter companies to also have Part 133 certificates as they sometimes engage in exterior (or swing load) operations.

Right now you are thinking, “Why can’t you just search by company in the NTSB database - like Guardian Flight - and it will present all accidents for tha company, regardless of classification?” In some cases yes, that does work. Searching for Guardian Flight brings up all four of the accidents I list here. But I have found in other cases it does not - something was not entered correctly and so an accident is overlooked. More importantly, I don’t know all the companies I am looking for, (the list of certificated Part 135 operators in the US is updated monthly with additions and subtractions happening constantly), so for my purposes, I need to cast a wide net.

Do you track in your database whether the investigation was actually performed by NTSB or an FAA Inspector? Curious how that correlates to what you’ve noted on who was listed as being interviewed (POI, etc.).

i think it is likely a natural response to feel unsettled. i haven't walked in those shoes, but i bet they'd fit. we continually benefit from an opportunity to re-invent ourselves, but the inertia can feel paralyzing. selfishly, i hope you keep writing. regardless, i will remain a steadfast fan.