On December 5, 2016, about an hour before his scheduled departure time of 9:30PM, Key Lime Air cargo pilot Lance McCaw told his company dispatcher that he was on a weather hold. Based in Panama City, FL and planning to fly to Albany, GA, he said he was dealing with “extreme” storms that had tornado activity. The dispatcher, as he later told NTSB investigators, believed he did not talk to McCaw again but the other Key Lime dispatcher working that night did. He phoned McCaw at 9:42PM to see if he was “planning on going”. He told investigators that the pilot responded, “I see some clear weather that I think I can fly towards the northeast, toward Albany.” Twelve minutes later, Flight 308 was in the air; twenty-eight minutes after that, it crashed and 39-year old McCaw was dead.

The NTSB determined the Probable Cause for the crash of Flight 308 was “the pilot's decision to initiate and continue the flight into known adverse weather conditions, which resulted in spatial disorientation, a loss of airplane control, and a subsequent in-flight breakup.”

Unsurprisingly, there was no mention in the Probable Cause of Key Lime Air’s operational control procedures, it’s risk mitigation procedures or the pattern of communications between company dispatchers, the pilot, and its customer, UPS. McCaw made the final decision to go and thus McCaw’s decision-making was responsible.

We need to talk about this accident.

Lance McCaw was the sole Key Lime Air employee based in Panama City. He had been flying Flight 308, operated in a Fairchild Metroliner, for eight years. It was scheduled Monday - Friday and he typically spent the night in Albany and returned to FL the next morning. His regular interactions with company personnel appeared to be via the dispatchers, based in Colorado, who pilots checked in with prior to departure. The dispatchers then monitored their progress using Flight Explorer software. Both dispatchers working the night of the accident told the NTSB that they had no power to cancel a flight. They were able to see the weather and follow the flights through Flight Explorer but mostly they served as point of contact if pilots had a maintenance or other concern. Dispatcher #1 also said after the flights reached their destination, pilots would “snap a picture through their phone” and send in a “log page” so he could input the arrival times that were later reported to UPS.

First, a word about dispatchers in Part 135. (For those who don’t know, this was my job for four years in Fairbanks, AK.) (And yep - I wrote a book about it.) As the Key Lime dispatchers made clear, they were actually flight followers or people who “follow” the flight via software and act as a primary contact for the pilots. (They were not licensed dispatchers.) (Neither was I.) From their descriptions to investigators of their duties however, the Key Lime night cargo dispatchers appear heavily focused on customer service. What’s tricky about Flight 308 is that while the dispatchers had no power over the flight, they were the only ones who spoke to the pilot. And as it happens, while he had responsibility for the flight’s completion, he was not the person the dispatchers spoke to the most about it.

Each dispatcher spoke to McCaw only once. After his initial call with him around 8:30PM where the delay was discussed, Dispatcher #1 spoke to a UPS representative three times that night — he could not remember the person’s name but did recall that all of the conversations were focused on issues surrounding Flight 308’s schedule. First, UPS wanted to know if the plane would make it to Albany, then they wanted to know again if the plane would make it into Albany as their employees were waiting there and had not seen it, and then they wanted to know where the plane was. After that third call, Dispatcher #1 told UPS he “wasn’t sure what was going on” and his flight tracker “showed the flight was supposed to go to Albany and that the destination had changed to Tallahassee”. At this point, the plane had crashed.

In the two hour window around Flight 308’s departure, Dispatcher #1 was responsible for eight other cargo flights.

Dispatcher #2 was not handling any Key Lime cargo flights the night of the accident but he answered the phone when UPS called ten minutes after departure time and the plane was still on the ground in Panama City. UPS told him that if the flight did not depart soon “the freight will not make service”. At this point Dispatcher #1 had already spoken to McCaw and registered the flight as on a weather hold. But Dispatcher #2 elected to call McCaw anyway, two minutes after he spoke to UPS. He explained they were looking for an update and that’s when McCaw told him he thought he could see a way around the weather and was immediately departing. If he couldn’t get through, he told the dispatcher he would use Tallahassee as an alternate. McCaw departed after this phone call, at 9:54 PM; he crashed less than half an hour later.

Even though Key Lime’s FAA-approved General Operations Manual required it, there was no Flight Risk Assessment Tool (FRAT) completed prior to the flight. This form typically includes a numerical assessment of various risk factors, including the weather, which when totaled determine if the flight is fine to go, should be discussed with management who has operational control, or should be canceled. The manual required every flight dispatcher to complete the FRAT prior to departure and store it for thirty days. The two dispatchers said they had never completed a FRAT for a night cargo flight nor were they told to do so. When the NTSB interviewed Key Lime’s management they could not explain why the forms were not completed for night cargo flights. (No one appears to have asked them how management failed to notice that there were no FRATs in the system for these flights.) They blamed the person who trained the two dispatchers with the oversight. (This person was no longer with the company and was not interviewed.)

And this brings us to operational control. The company’s manual is required to explain what persons are authorized to hold operational control. It typically is the Director of Operations, Chief Pilot, Safety Manager, etc. and their job is to be responsible for the operational decision-making on a flight. (The pilot ultimately has go/no go but this is the person who participates in that decision if there are issues with things like weather. They should know if a flight is delayed and/or canceled.) If the risk assessment says there is an issue, this is the person who is contacted. With Flight 308 on weather hold, the person with operational control would typically have been contacted and probably would have spoken directly to the pilot. In the very few, very short interview summaries attached to the Flight 308 accident docket, there is no evidence that anyone at Key Lime was asked about operational control. Here’s what the accident report had to say on that subject:

So, the Director of Operations had operational control over all operations, the dispatchers had it for scheduling and following and the Pilot-In-Command had it for the safe completion of the flights. In actual practice, it appears that the pilot made all the decisions for the flight and the dispatchers dealt with the very powerful customer who wanted the flight to go and then talked directly to the pilot about what that customer wanted them to do and no one else was at the company was involved.

The company’s Technical Programs Director (this is an odd title) told investigators that if a pilot canceled a flight due to weather there was no action taken against that pilot. As to how UPS would react, he said “Flights canceled due to weather do not count against the carrier reliability metrics. KLA [Key Lime Air] is only paid when the aircraft moves. In the case of a weather cancellation, KLA will, in effect, still be paid since the freight will eventually be moved once the WX is acceptable. Flights canceled due to mechanical or pilot issues count against the carrier reliability metrics used by UPS for evaluating its feeders.”

It is worth remembering that UPS phoned Key Lime four times after Flight 308 missed its departure time to inquire about its status. UPS had employees waiting, and they wanted Key Lime to know it. In return, Key Lime’s dispatchers made sure that McCaw knew that as well.

Night instrument meteorological conditions prevailed in Panama City and the flight was conducted under instrument flight rules (IFR) when it departed at 9:54PM. (This was twelve minutes after Dispatcher #2 informed McCaw that UPS was concerned.) Twenty-one minutes after departure, air traffic control informed McCaw of a "ragged line of moderate, heavy, and extreme precipitation” along his route. A descent to 3,000 feet was approved and ATC advised of another route that might skirt the weather. McCaw responded that he would check that after the descent. About two minutes later he said he wanted to deviate to the right of his course and was cleared to turn right or left as needed. He then said he wanted to turn back to Tallahassee and was cleared direct to the airport and offered any altitude. ATC recommended a heading of 180 degrees which the pilot accepted. At 10:20 radar showed the aircraft at about 3,500 feet as it began a right turn that continued 540 degrees; radar contact was lost at 10:22.

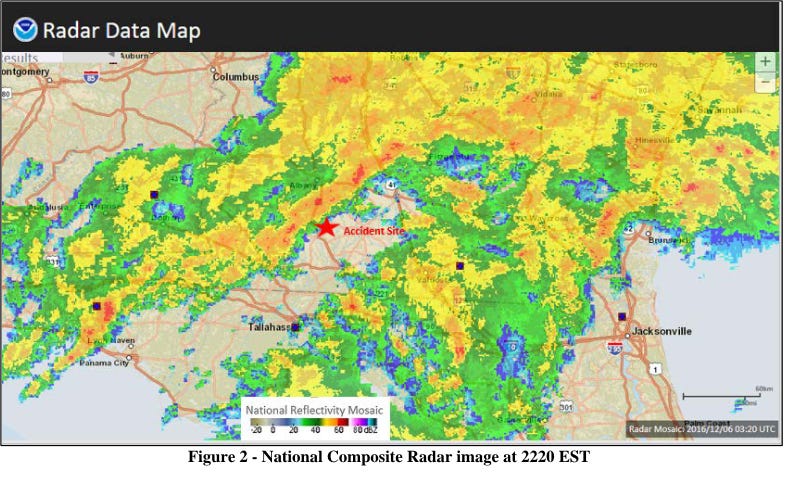

This is a Nation Weather Service composite radar map of storms from that night.

At 10:55PM, UPS made its fourth phone call to Key Lime dispatch asking about the flight. Dispatcher #1 noticed its last destination was set at Tallahassee and phoned the tower there which informed him there was no record of 308’s arrival. At 11:03PM he then contacted Jacksonville Center and asked if they knew where the plane was. That is when he was told Flight 308 crashed.

Flight Explorer had indicated the flight “aged out” at 10:28; the dispatcher, whose primary duty was to follow Flight 308, had not noticed.

There is only one brief note from a FAA Aviation Safety Inspector in the accident docket. He spoke with McCaw on the phone the day of the accident and was in Panama City to inspect airworthiness paperwork, etc. He was not the company’s Principal Operations Inspector. The POI, Harvey Haynes, who might have been able to shed light on risk assessment procedures for night cargo flights, operational oversight and the interactions between UPS, dispatch, and pilots, gave a brief interview — only two sentences from it are included in the document:

No one at UPS was interviewed.

Key Lime promised the NTSB it would extend risk assessment forms to night cargo in the wake of the accident. As to why a pilot intimately familiar with the region, with over 8,400 hours of total time (and 4,670 in the aircraft), chose to depart in such challenging weather, no one had anything to say and its not clear the NTSB even asked.

The impact of customer pressure on a company can be significant, especially when the customer creates an economic footprint the size of UPS. In accident investigations the NTSB does not look deep into the relationship between UPS (or FedEx) and its feeder airlines, however. When I started analyzing Part 135 cargo accidents for an article last fall at AIN, I found sporadic mention of the customers in the accident reports but plenty of reasons to look further. Ameriflight had the most accidents between 2013-2022, it is a feeder for UPS, FedEx and DHL. Martinaire had the second-most, it is a UPS feeder. Wiggins Airways, Ameriflight’s sister company, crashed in New Hampshire in January of this year seriously injuring the pilot. Wiggins is also is a feeder for UPS and FedEx.

I’m sure I could go on and on with more research.

There’s a potential pattern here, and I think someone should be looking into it. Pressure is a complicated thing to understand (and investigate) but the fact that it exists is why firewalls between customers and pilots are so necessary. It’s part of why strong operational control at a managerial level is so important and why the responsibility for delays should be shared by multiple company personnel.

As to Key Lime Air, per an NTSB interview two months after the crash, the company stated that it was no longer operating the Panama City - Albany route. They did not explain if this was their decision, or one that was made for them by UPS. Flight 308 thus no longer existed.

I’m waiting on some newly sorted documents on the 1932 Cosmic Ray Expedition from Princeton, so hopefully a bit about that in the near future!

Great article. You're right, the pressure applied to fly by customers can be a real problem. Pilots should be trained to deal with it.