I spend an inordinate amount of time in the National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) aviation accident database. I’m such a regular there that I was asked to beta test their new design before it rolled out a couple of years ago. (I am ridiculously proud of this fact.) Spending so much time in it means that I know a lot about what does and doesn’t work there and how the subtleties of the aviation regulations can play into what you learn from the database. Recently, I’ve been building my own spreadsheet of Part 135-involved accidents in the U.S. and I wanted to share how it’s going and some of the quirks I’ve found along the way.

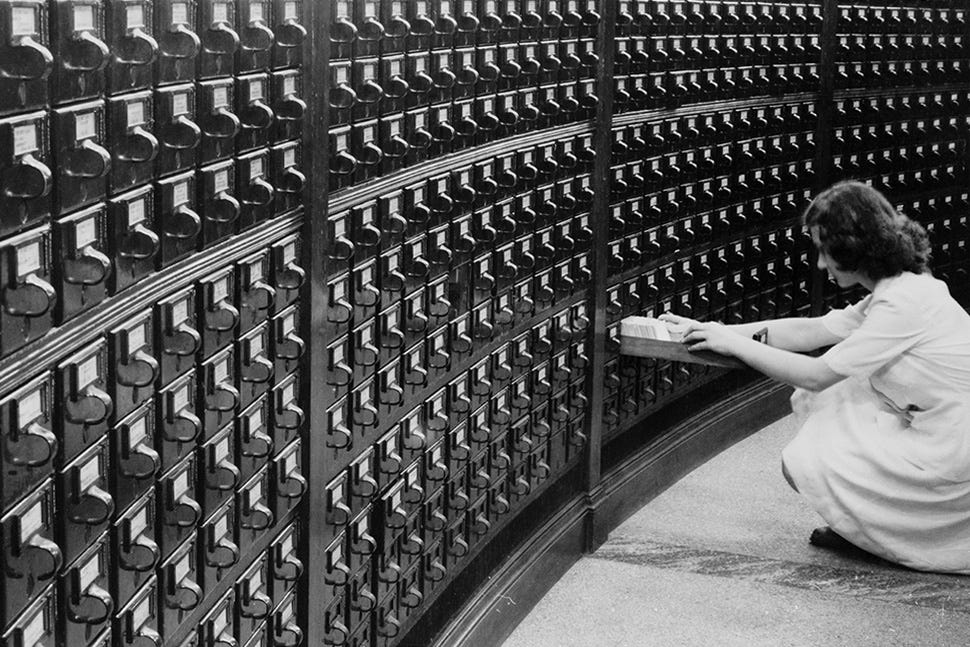

First, I miss card catalogs.

I know that they were inefficient in comparison to just typing words into an online database, BUT there is a false sense of security that comes from using online databases. Lots of folks think the search engine is finding everything they are looking for (like all accidents involving Part 135 operators in a year) which is not necessarily the case. (It’s all in how you ask and where you look.)

Plus, card catalogs are cool and that will never change.

I started spending serious time in the NTSB database because I had a lot of questions about commercial accidents in Alaska. The same sort of crashes have been happening for Part 135 (i.e. commercial companies flying smaller aircraft) for decades, and the commonly acknowledged reason was excessive risk-taking or “bush pilot syndrome” on the part of pilots. (The NTSB talked about the syndrome in both 1980 and 1995 studies on AK.) This belief was so prevalant among federal inspectors and investigators that when I wrote my graduate thesis in 1999 it was called “Just One More Dead Pilot”. (There’s a long explanatory subtitle I won’t bore you with.)

I knew pilots who were in accidents in the 1990s and I know some did stupid things, but also some got crappy training, some flew for crappy companies with crappy airplanes, some were so new they never should have been dispatched on the flights they were sent on, and some were facing a ridiculous amount of pressure from many different directions (but mostly their crappy bosses).

Some of this stuff I ended up writing about in my memoir, The Map of My Dead Pilots.

But I wanted actual data to study and to see who the companies were that repeatedly had accidents. If this was all about pilots taking risks then after those pilots were killed, the aviation environment should have gotten safer. It did not. I wanted to see who the repeat offender companies were, and what the NTSB and FAA were doing about them.

So, I created a database of every single Part 135-involved accident from 1990 - forward. (It is now thru 2023.) First it was just date, companies, location, #fatalities and/or serious injuries, pilot flight time and type of operation (more on that in a moment). I’m constantly working on this thing though, as I find something else I want to know. Pretty quickly, I learned this:

There is no disputing that Hageland Aviation had a problem.

As Alaskan readers know, Hageland was part of the April 2020 bankruptcy of Ravn Air Group; during which Hageland was sold and is no longer in business. (That’s a long story.) At one time, however it was one of the largest scheduled Part 135 operators in the U.S. To give you an idea, in 2015 Hageland flew 26,267,293 pounds of mail and 259,247 passengers. (All of that was just in AK.) (Plus freight which I haven’t looked up.) However, the company crashed — a lot. The disheartening thing is that most of these accidents, even the fatal ones, resulted in few documents in the accident dockets, almost no company interviews, and little formal interviewing with the FAA. This was a particular problem because lack of FAA oversight is part of a pattern I found not only with Hageland, but throughout the accidents I studied.

(This might also have you thinking about Boeing right now.)

It’s not that the FAA didn’t care — they are just strung way too thin in AK. (In one of the only FAA interviews in a docket, for the 2013 St Marys accident, the company’s principal operations inspector talked about how he requested more help from his superiors in the lower 48 and was refused.) (The refusal had to do with it being Part 135 - Part 135 was not percevied as important/significant compared to the big Part 121 airlines and thus not worth the attention of more FAA inspectors.)

Anyway, the more I poured over the accidents, including even those when the companies were flying empty or in training (thus under Part 91 - aviation types will understand this), the more patterns emerged. I saw the companies that had the same problems over and over, I saw the locations that were hit the hardest and I saw that for every low time accident pilot of 600-700 hours, there would be a high time pilot of 10,000-15,000 hours and many more in the mid-range. The database showed me so much that had not been discussed in the past, it just took a lot of time to get the pertinent information out.

You can not, for example, just put in a company name and be guaranteed you are getting all of its accidents. Sometimes, their dba is entered and sometimes it isn’t, and sometimes they change names but not ownership. Also, sometimes it is the exact same name but very different ownership, so you need to know about that. And you have to watch for companies with common ownership. In my article that was published by AIN late last year on U.S. Part 135 cargo accidents I missed that Ameriflight also owned Wiggins Airways. They are separate companies but common ownership and thus could have corporate safety culture overlap. I missed it and didn’t realize the ownership until Wiggins crashed in January and the aircraft was obviously one from Ameriflight. I wasn’t careful enough back when I researched the cargo article.

Another thing is that you have to capture all Part 91 accidents that involve Part 135 operators if you want a true picture of a company’s activities. This means you have to look at ALL THE ACCIDENT REPORTS. Yes, it is tedious as hell. It took months to get this massive AK database built. For the entire US, I only have two years in (2022 and 2023), with a goal of getting ten years. Again - the plan is to see who has a history of accidents - companies, types of operation, types of aircraft, etc. Here’s one thing that has jumped out at me so far:

That’s two years of medevac accidents (the first number column is fatalities, the second is serious injuries). These are very recent so most are only in preliminary investigation status. Reach Air Medical was a bird strike (these are more common than you might think), the red Air Methods accident was a fueler who failed to ground the aircraft and injured himself and one of the Air Evac accidents involved a lithium battery explosion in a paramedic’s pocket (that was wild to read about). Sooo…not all accidents involve the pilot, company or operation. Some really are “accidents”. But most of them aren’t like those; most involve operational, training or maintenance errors. And I can see the medevac is an area with a lot of those errors. The question is why. (And guess what - very few medevac accidents in Alaska!) I need more info in the database before I will know. (I am working on a separate medevac database now because of this.) (Of course!)

Enough of all this for now. The main point was to show what can be learned from the NTSB accident database, but you really need to know aviation in order to get the most/best info out of it. We are so lucky to have this resource though and it has had a big impact on everything I’ve written.

If you like my newsletter, I would appreciate it you let your followers know that it exists and, if you can, subscribe or upgrade to paid. As soon as I have news on the lawsuit against me, I’ll let you know more on how those dollars have been spent.

Keep up the good work.